By Frank Gavurin

We spend billions each year switching wind turbines off when there’s too much renewable energy for the grid to move long distances. We could be making creative use of that energy instead.

Why so much renewable energy is wasted

The renewable transition, in the UK and across the world, is already happening. But the speed at which it takes place is crucial. Each fraction of a degree of warming is a question of thousands of lives saved or lost. In this context, the thought of huge amounts of clean, carbon-free energy being wasted is maddening.

Britain’s blustery conditions make it an ideal place to generate electricity – wind, and to a lesser degree solar, now account for roughly a third of electricity generation in the UK, up from just 10% in 2014. Our outdated grid, however, has failed to keep up with the increase in renewable production; sometimes it simply does not have the capacity to transport it from the places it is generated to the places with highest demand for electricity. The grid and distribution companies are putting profit ahead of updating our energy system.

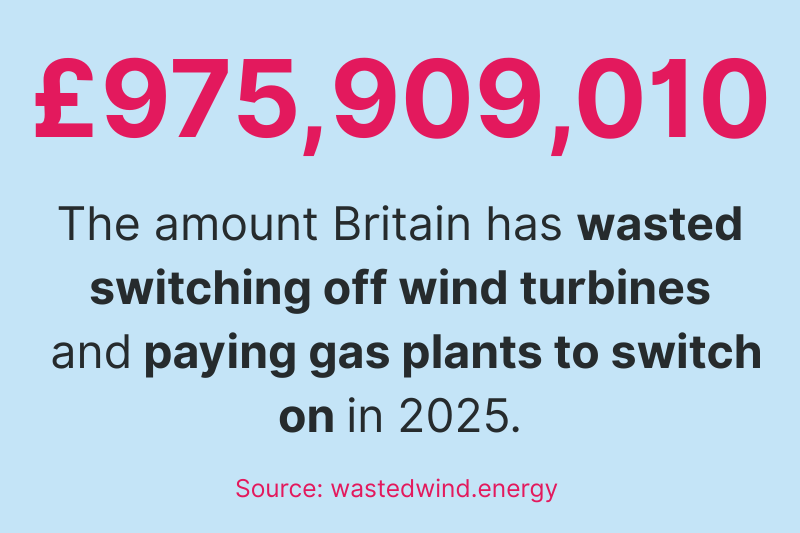

The result of this is what is known as ‘curtailment’: essentially, operators of wind and solar farms being paid to turn off when there is excess wind or sun. Octopus Energy has recently launched a very handy tracker to show how much money the UK wastes on turning off our wind turbines and switching on gas stations closer to demand. At the time of writing, Britain has spent £975,909,010 doing so this year – yesterday alone, the cost was over six million pounds.

Why it matters

If this seems irrational, it’s because it is. The economic cost alone is reason enough to oppose this wastefulness. But at a time when UK public support for renewables is beginning to fall1, it is key to combat one of the fossil-fuel-funded right’s arguments.

Boosting the grid’s capacity is of course a key part of the solution. After all, sparsely populated Scotland generates nearly 50% of the UK’s wind power, which is enough to power over 26 million homes. Some of this energy simply needs to get to places with more people and therefore more demand for electricity.

But these grid improvements will take a while and an increasingly renewables-sceptical public won’t see the benefits immediately. What they will see are headlines claiming that green technologies are in fact driving bills up. Stopping this wastage is an urgent task.

While the UK has introduced several “energy flexibility” initiatives to start to use some of this excess energy, this has mainly benefited corporates and affluent households with EVs and batteries to store this cheap or free energy. Most households are missing out completely.

How other countries have tackled the problem

There is an urgent need to find fairer ways of sharing excess renewable energy with those that need it most, whether that’s directly to individuals or via municipal district heating schemes. This is something which has already been tried with success in various places across Europe.

In Vienna, for example, a power-to-heat plant (essentially a massive boiler) built in 2017 has used excess renewable electricity to provide hot water for up to 20,000 households through the city’s district heating network. It can be activated in as little as five minutes to quickly respond to surpluses, and was successful enough that the city has invested in another power-to-heat facility to decrease wastage of renewable energy even further.

More recently in Hamburg, Germany, another power-to-heat unit became the first in the country to take advantage of legislation introduced in 2023 to prevent wastage of renewable energy. The municipal energy provider has signed a contract with the regional transmission system operator to use electricity that would otherwise be wasted to power a district heating system. This is expected to reduce CO2 emissions by 4,000 tonnes per year and lower redispatch costs – the cost of turning on other, more expensive sources to make up for lost renewable production – by around €800,000 per year.

These facilities can indirectly reduce bills by reducing wastage and lowering the amount of expensive and polluting fossil fuels we need to burn to meet our needs.

A more direct way of demonstrating the benefits of renewables, however, is giving people free energy. And far from being an abstract or utopian goal, this is already happening.

In Northern Ireland, for example, not-for-profit social enterprise EnergyCloud has partnered with the Northern Ireland Housing Executive to provide some households in social housing with free hot water heated by surplus renewable power. EnergyCloud has been active in the Republic of Ireland since 2023, while its first project in England, targeted at fuel-poor households, was announced this summer.

How you can help

Clearly, then, there are ways we can make the most of the renewables we already have. It’s a no-brainer: save carbon, save the consumer money, and stop providing bad faith actors ammunition with which to attack the green transition. In order to do this, though, we need government action. And in order for this government to act, there needs to be pressure. That’s where you come in.

1) Write to FPA to get involved with our Fair Wind campaigning

You can fill in our contact form below with the subject ‘Fair Wind’. Let us know that you can join in and help shape our campaigning.

2) Affiliate your union

Take a model motion to your union branch to build support for our Energy For All campaigning.

And read our What You Can Do page for more ways to get involved!

Frank Gavurin is a Fuel Poverty Action member. He is a Politics and Spanish graduate and is currently studying a master’s in Modern History.

- 88% of the public supported or strongly supported use of renewable energy in autumn 2022, whereas by spring 2025 only 80% did, while opposition or strong opposition doubled from 2% to 4% in this time ↩︎